How reality TV has changed the way we think

BBC

BBCIt was 17 August 2000 and a gaggle of individuals had been huddled round a pc display screen within the BBC TV newsroom, when instantly there got here a collective gasp. One of many group rotated and introduced, very solemnly: “Nasty Nick’s gone.”

Nick Bateman – a housemate within the UK actuality TV present Huge Brother – was discovered to have tried to “manipulate” his fellow contestant’s votes, and was requested to depart the truth TV home. It might turn into front-page information.

The saga prompted a nationwide ethical debate, not solely concerning the incident however the very existence of the present.

Writing for the London Night Commonplace one TV critic accused Huge Brother’s prime govt Peter Bazalgette of “smearing excrement over our screens”.

A reviewer from The Herald newspaper denounced the housemates as “fakers, chancers, dullards, no-marks, and dimwits”.

But Britons voted with their toes (or their distant controls). Some 10 million individuals tuned in for the finale on 15 September – marking the beginning of a serious cultural shift.

Press Affiliation

Press AffiliationNow, 25 years on, actuality TV is without doubt one of the hottest genres on screens within the UK.

The Traitors attracted greater than 10 million viewers for the opening episode of third collection in January. And Love Island UK could have seen audiences shrink since its episode peak of six million in 2019, however it has nonetheless been renewed 10 instances.

For years, the darkish sides of actuality TV have been unpicked. There have been regarding, in some circumstances devastating, impacts on the contestants of sure reveals, which has rightly prompted change.

As for critics, some have continued to dismiss many actuality TV reveals as superficial escapism, at finest – or, at worst, harmfully divisive.

Hear carefully, nonetheless, and a small clutch of psychologists and social specialists are quietly beginning to inform a special story – one that implies that the impression of watching actuality TV may not be as dangerous for brains (or social consciences) as it could appear.

Getty Photographs/ Press Affiliation

Getty Photographs/ Press AffiliationSome counsel that it may assist viewers construct a greater grasp of views exterior our realm of expertise, and even overcome biases.

“Actuality TV has traditionally been extra numerous demographically than different types of media,” says Danielle Lindemann, a sociology professor at Lehigh College, Pennsylvania.

“[It] casts a highlight over patches of the social panorama that we do not at all times see, so in that means, it may be a device for higher social understanding.”

A glimpse backstage

The UK Huge Brother, based mostly on a Dutch tv collection of the identical identify, introduced collectively a gaggle of 10 strangers in a home in London.

For 64 days, contestants had been sealed off from the skin world and their each transfer filmed, with viewers voting out roughly one individual every week till a winner was handed the £70,000 prize.

What was actually revolutionary wasn’t the competitors format however the connection between the audiences and the peculiar individuals whose lives inside the home performed out on display screen.

“That did not exist earlier than,” says Dr Jacob Johanssen, affiliate professor of communications at St Mary’s College, who researches the psychological results of actuality TV.

“For the primary time, viewers began seeing peculiar individuals on tv who weren’t celebrities, which is a really totally different phenomenon.”

ITV/PA Wire

ITV/PA WireImmediately actuality TV covers a broad spectrum — from fly-on-the-wall dramas that doc the lives of associates (The Solely Method is Essex, Geordie Shore, Made in Chelsea) to competition-based reveals (Survivor, The Traitors, Love Island) that revolve across the ‘actuality’ of contestants’ lives.

However its energy stays the identical – every provides a glimpse into the dramas of actual peoples’ lives – an opportunity to see backstage.

“You do see plenty of unfiltered, uncooked feelings… in these totally different programmes,” continues Dr Johanssen. “If we see them in actual life, often that might occur within the non-public sphere, actually not in public.”

‘Folks really feel much less remoted or alienated’

Dr Johanssen has labored on the truth present Embarrassing Our bodies, which options sufferers consulting with docs, aiming to destigmatise widespread well being complaints.

As he sees it, “despite the fact that there are many problematic elements to it, it made individuals conscious there are totally different sorts of physique varieties, there are totally different circumstances individuals may need.

“It maybe made individuals really feel much less remoted or alienated.”

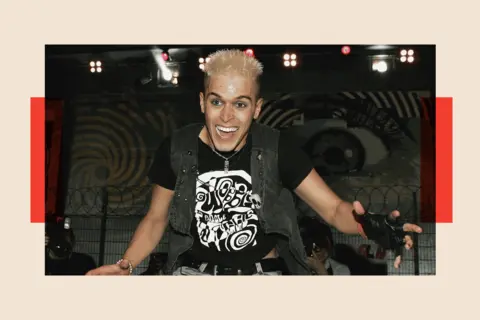

The identical can go for incapacity consciousness. Pete Bennett, the winner of the 2006 collection of Huge Brother, was a livewire character who received over the general public, additionally occurred to have Tourette’s syndrome.

His look on the present felt groundbreaking at a time when incapacity consciousness and illustration within the UK was nowhere close to present understanding – and it gave sufficient display screen time for a mass viewers to each be launched to Tourette’s, but in addition heat to Pete.

“I might get bullied rather a lot with Tourette’s,” Pete defined of his time earlier than Huge Brother. “I could not actually exit and luxuriate in myself with out being ridiculed or began on due to my ticks.”

However he provides: “I’ve by no means been bullied since leaving the home.”

Getty Photographs

Getty PhotographsThen there are the conversations about uncomfortable, and generally controversial, topics that contestants have delved into too – in some circumstances a lightning rod for nationwide discussions.

Through the years, a number of Love Island contestants have been accused of “gaslighting,” a possible type of coercive management, which is a legal offence. It has prompted a lot dialogue on social media, in a single occasion main Ladies’s Support to launch an announcement.

Prof Helen Wooden of Lancaster College, who researches and advises on the ethics and practices of actuality TV, recollects a separate dialogue about home abuse and argues that elevating this is usually a optimistic.

“I keep in mind a giant debate about Love Island and whether or not it permits… a dialog on what home abuse appears to be like like?” she says. “For some audiences that might be triggering, for some audiences that might be useful.”

Insights into social cues… and deception

Faye Winter was 26 when she appeared on Love Island. She labored as a lettings supervisor on the time, however lamented there have been, as she noticed it, “no match males in Devon”, the place she lived, so she utilized for the present and joined the 2021 collection.

Shortly, she partnered up with Teddy Soares, a monetary advisor initially from Manchester.

“From a lady’s standpoint, they’ll must get used to me stirring just a few pots and inflicting a little bit of a ruckus,” he instructed ITV after signing up.

Getty Photographs

Getty PhotographsThe promised ruckus quickly materialised, after Faye was proven a clip by which Teddy admitted to being sexually attracted to a different contestant.

Her heated, expletive-filled shouts, by which she referred to as Teddy two-faced, prompted nearly 25,000 complaints to Ofcom.

Some thought-about her response disrespectful and an “overreaction”. But different viewers strongly recognized along with her.

“I obtained a number of trolling for it,” she later instructed a newspaper. “[But] I obtained lots of people who mentioned they have been by it”.

Dr Rosie Jahng, an affiliate professor of communications from Wayne State College in Michigan, believes that the insights supplied by actuality TV into social cues, physique language, and deception, will be helpful.

“It turns into like testing an ethical boundary – we begin to ask, ‘what would I do in that state of affairs?'”

When actuality TV turns into ‘constructed’ actuality

Understanding how others react in conditions can in itself be informative, or immediate self-reflection. However what occurs when actuality TV deviates away from documented actuality to a murkier sort of “constructed” actuality?

A former Made in Chelsea solid member beforehand defined the way it labored when she was on the present.

“The producers spoke to us on the cellphone for hours each week,” Francesca “Cheska” Hull, who appeared from the primary collection, earlier mentioned in an interview.

“They’d come on nights out with us. They put us in conditions that created drama.”

Getty Photographs

Getty PhotographsShe pressured that scripts weren’t used however added, “You knew the conversations you needed to have”.

On the floor, at the least, this appears to deviate from the thought of following uncooked feelings. However psychologists have prompt that even constructed actuality can have advantages.

“It may possibly probably provide advantages to viewers and society as a result of it may well result in wider conversations concerning the world we wish to dwell in,” argues Dr Johanssen. “As an example relating to problematic or unethical behaviour or questions of gender identification and inequality for instance.”

The darker facet of actuality TV

The experiences of people that seem on the reveals, nonetheless, raises a wholly totally different set of questions.

“We’ve got to separate out the worth of a present sparking a dialog and what’s occurring to individuals,” explains Prof Wooden. “Quite a lot of reveals, particularly early reveals, had been about placing individuals in very tough conditions that had been trauma-inducing.”

Through the 2007 collection of Superstar Huge Brother, actress Shilpa Shetty discovered herself on the centre of a race and bullying row, after a fellow contestant referred to as her “Shilpa poppadum”.

The incident sparked a nationwide dialog about racism.

Press Affiliation

Press Affiliation“With the Shilpa Shetty case… there have been plenty of complaints the place individuals felt somebody was being bullied or not being handled effectively on display screen,” says Prof Wooden.

“I believe that second enabled a kind of shift. We do not wish to see that anymore.”

Extra lately, some Love Island contestants have spoken about their experiences of poor psychological well being following the present, in addition to struggles with the relentless scrutiny.

A UK parliamentary committee carried out an inquiry into actuality TV in 2019, and mentioned its “choice to launch the inquiry into actuality TV comes after the loss of life of a visitor following filming for The Jeremy Kyle Present and the deaths of two former contestants within the actuality courting present Love Island”.

PA Media

PA Media“We’re nonetheless not there when it comes to whether or not individuals are utterly adequately cared for,” argues Dr Johanssen, who submitted proof to the inquiry.

“They don’t have any company or management over the edit, or what an episode appears to be like like, how someone is portrayed.”

Nonetheless, Love Island’s producers have mentioned they’ve realized how you can higher help the solid and crew. Revised welfare measures have been launched together with specialised social media coaching for contestants, in addition to video coaching and steerage on subjects together with coercive behaviour and avoiding discriminatory language.

Ofcom additionally established new guidelines to guard these showing on TV and radio actuality reveals, following a gentle rise in complaints over the welfare of friends — saying broadcasters should “correctly take care of” contributors, notably those that is likely to be liable to “important hurt” because of collaborating.

“Quite a lot of the broadcasters are saying to us that there is a shift in temper,” provides Prof Wooden, who’s engaged on a analysis undertaking care practices in UK actuality TV.

“They need individuals… to get one thing higher out of it than they’d have previously.”

Reflecting society again at itself – or shaping it?

The query that continues to be, nonetheless, is what the collective impression is. Is actuality TV simply holding up a mirror to society, or may it actually play an energetic half in shaping it?

Prof Lindemann believes that there are examples of optimistic connections between the fabric on actuality reveals and the way viewers have interaction with the world.

Even way back to 2011, it was discovered to be having an impact on behaviour.

Press Affiliation

Press AffiliationShe factors to at least one US research which discovered that ladies who watched courting reveals like Temptation Island, The Bachelor, or Joe Millionaire had been extra prone to speak with each other about intercourse.

In 2014, a paper was printed, cowritten Melissa Kearney an affiliate professor of economics on the College of Maryland, that drew hyperlinks between a discount in teenage start charges within the US, and the airing of a actuality collection on MTV referred to as 16 and Pregnant, which supplied a brutally sincere have a look at life for pregnant youngsters.

This present “was not particularly designed as an anti-teen childbearing marketing campaign,” wrote the authors, “however it appears to have had that impact by displaying that being a pregnant teen and a brand new mom is tough.”

They concluded: “We discover that media has the potential to be a robust driver of social outcomes.”

One decade on, that actually hasn’t modified. Which makes actuality tv a robust device. In some circumstances that device is highly effective for the more severe – however simply generally, it actually may form these watching it for the higher.

Prime image credit score: ITV/PA Wire

BBC InDepth is the house on the web site and app for one of the best evaluation, with contemporary views that problem assumptions and deep reporting on the largest problems with the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content material from throughout BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You may ship us your suggestions on the InDepth part by clicking on the button beneath.

2025-07-25 23:11:00